Find first set

In software, find first set (ffs) or find first one is a bit operation that, given an unsigned machine word, identifies the index or position of the least significant set bit (or one bit) in the word. A nearly equivalent operation is count trailing zeros (ctz) or number of trailing zeros (ntz), which counts the number of zero bits following the least significant one bit. The complementary operation that finds the index or position of the most significant set bit is log base 2, so called because it computes the binary logarithm  .[1] This is closely related to count leading zeros (clz) or number of leading zeros (nlz), which counts the number of zero bits preceding the most significant one bit. These four operations also have negated versions:

.[1] This is closely related to count leading zeros (clz) or number of leading zeros (nlz), which counts the number of zero bits preceding the most significant one bit. These four operations also have negated versions:

- find first zero (ffz), which identifies the index of the least significant zero bit;

- count trailing ones, which counts the number of one bits following the least significant zero bit.

- count leading ones, which counts the number of one bits preceding the most significant zero bit;

- The operation that finds the index of the most significant zero bit, which does not have a common name.

There are two common variants of find first set, the POSIX definition which starts indexing of bits at 1,[2] herein labelled ffs, and the variant which starts indexing of bits at zero, which is equivalent to ctz and so will be called by that name.

Contents |

Examples

Given the following 32-bit word:

- 00000000000000001000000000001000

The count trailing zeros operation would return 3, while the count leading zeros operation returns 16. The count leading zeros operation depends on the word size: if this 32-bit word were truncated to a 16-bit word, count leading zeros would return zero. The find first set operation ffs would return 4, indicating the 4th position from the right. The log base 2 is 15.

Similarly, given the following 32-bit word, the bitwise negation of the above word:

- 11111111111111110111111111110111

The count trailing ones operation would return 3, the count leading ones operation would return 16, and the find first zero operation ffz would return 4.

If the word is zero (no bits set), count leading zeros/count trailing zeros both return the number of bits in the word, while ffs returns zero. Both log base 2 and zero-based implementations of find first set generally return an undefined result for the zero word.

Hardware support

Many architectures include instructions to rapidly perform find first set and/or related operations, listed below. The most common operation is count leading zeros (clz), likely because all other operations can be implemented efficiently in terms of it (see Properties and relations).

| Platform | Mnemonic | Name | Word sizes | Description | Result on zero input |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intel 386 and later | bsf[3] | Bit Scan Forward | 16, 32, 64 | ctz | Undefined, sets zero flag |

| Intel 386 and later | bsr[3] | Bit Scan Reverse | 16, 32, 64 | log base 2 | Undefined, sets zero flag |

| AMD supporting SSE4.2 | lzcnt[4] | Count Leading Zeros | 16, 32, 64 | clz | input size, sets carry flag |

| Itanium | clz[5] | Count Leading Zeros | 64 | clz | 64 |

| ARM 5 or later | clz[6] | Count Leading Zeros | 32 | clz | 32 |

| IBM POWER/PowerPC | cntlz/cntlzw/cntlzd[7] | Count Leading Zeros | 32, 64 | clz | input size |

| MIPS | clz[8][9] | Count Leading Zeros in Word | 32, 64 | clz | input size |

| MIPS | clo[8][9] | Count Leading Ones in Word | 32, 64 | clo | input size |

| DEC Alpha | ctlz[10] | Count Leading Zero | 64 | clz | 64 |

| DEC Alpha | cttz[10] | Count Trailing Zero | 64 | ctz | 64 |

| Motorola 68020 and later | bfffo[11] | Find First One in Bit Field | arbitrary | log base 2 | field offset + field width |

Notes: On some Alpha platforms CTLZ and CTTZ are emulated in software.

Tool and library support

A number of compiler and library vendors supply compiler intrinsics or library functions to perform find first set and/or related operations, which are frequently implemented in terms of the hardware instructions above:

| Tool/library | Name | Type | Input type(s) | Notes | Result for zero input |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| POSIX.1 compliant libc 4.3BSD libc OS X 10.3 libc[2][12] |

ffs |

Library function | int | Includes glibc. POSIX does not supply the complementary log base 2 / clz. |

0 |

| FreeBSD 5.3 libc OS X 10.4 libc[13] |

ffsl |

Library function | int, long | fls ("find last set") computes (log base 2) + 1. | 0 |

| FreeBSD 7.1 libc[14] | ffsll, flsll |

Library function | long long | 0 | |

| GCC 3.2.2[15][16] | __builtin_ffs |

Built-in functions | unsigned int, unsigned long, unsigned long long |

Possibly available before 3.2.2. | 0 |

__builtin_ctz |

undefined | ||||

__builtin_clz |

undefined | ||||

| Visual Studio 2005 | _BitScanForward[17]_BitScanReverse[18] |

Compiler intrinsics | unsigned long, unsigned __int64 |

Returns zero on zero input, unlike x86 bsf/bsr | 0 |

| Visual Studio 2008 | __lzcnt[19] |

Compiler intrinsic | unsigned short, unsigned int, unsigned __int64 |

Relies on AMD-only lzcnt instruction | Input size in bits |

| Intel C++ Compiler | _bit_scan_forward[20] |

Compiler intrinsics | int | undefined | |

| NVIDIA CUDA[21] | __clz |

Functions | 32-bit, 64-bit | Compiles to fewer instructions on the GeForce 400 Series | 32 |

__ffs |

0 | ||||

| LLVM | llvm.ctlz.*llvm.cttz.*[22] |

Intrinsic | 8, 16, 32, 64, 256 | LLVM assembly language | Input size if arg 2 is 0, else undefined |

Properties and relations

The count trailing zeros and find first set operations are related by ctz(x) = ffs(x) - 1 (except for the zero input). Given w bits per word, the log base 2 is easily computed from the clz and vice versa by lg(x) = w - 1 - clz(x).

As demonstrated in the example above, the find first zero, count leading ones, and count trailing ones operations can be implemented by negating the input and using find first set, count leading zeros, and count trailing zeros. The reverse is also true.

On platforms with an efficient log base 2 operation such as M68000, ctz can be computed by:

- ctz(x) = lg(x & (-x))

where "&" denotes bitwise AND and "-x" denotes the negative of x treating x as a signed integer in twos complement arithmetic. The expression x & (-x) clears all but the least-significant 1 bit, so that the most- and least-significant 1 bit are the same.

On platforms with an efficient count leading zeros operation such as ARM and PowerPC, ffs can be computed by:

- ffs(x) = w - clz(x & (-x)).

Conversely, clz can be computed using ctz by first rounding up to the nearest power of two using shifts and bitwise ORs,[23] as in this 32-bit example (note that this example depends on ctz returning 32 for the zero input):

function clz(x):

for each y in {1, 2, 4, 8, 16}: x ← x | (x >> y)

return 32 - ctz(x + 1)

On platforms with an efficient Hamming weight (population count) operation such as SPARC's POPC or Blackfin's ONES,[24] ctz can be computed using the identity:[25][26]

- ctz(x) = pop((x & (-x)) - 1),

ffs can be computed using:[27]

- ffs(x) = pop(x ^ (~(-x)))

where "^" denotes bitwise xor, and clz can be computed by:

function clz(x):

for each y in {1, 2, 4, 8, 16}: x ← x | (x >> y)

return 32 - pop(x)

The inverse problem (given i, produce an x such that ctz(x)=i) can be computed with a left-shift (1 << i).

Find first set and related operations can be extended to arbitrarily large bit arrays in a straightforward manner by starting at one end and proceeding until a word that is not all-zero (for ffs/ctz/clz) or not all-one (for ffz/clo/cto) is encountered. A tree data structure that recursively uses bitmaps to track which words are nonzero can accelerate this.

Algorithms

Where find first set or a related function is not available in hardware, it must be implemented in software. The simplest implementation of ffs uses a loop:

function ffs (x)

if x = 0 return 0

t ← 1

r ← 1

while (x & t) = 0

t ← t << 1

r ← r + 1

return r

where "<<" denotes left-shift. Similar loops can be used to implement all the related operations. On modern architectures this loop is inefficient due to a large number of conditional branches. A lookup table can eliminate most of these:

table[0..2n-1] = ffs(i) for i in 0..2n-1

function ffs_table (x)

if x = 0 return 0

r ← 0

loop

if (x & (2n-1)) ≠ 0

return r + table[x & (2n-1)]

x ← x >> n

r ← r + n

The parameter n is fixed (typically 8) and represents a time-space tradeoff. The loop may also be fully unrolled.

An algorithm for 32-bit ctz by Leiserson, Prokop, and Randall uses de Bruijn sequences to construct a minimal perfect hash function that eliminates all branches:[28]

table[0..31] initialized by: for i from 0 to 31: table[(0x077CB531 << i) >> 27] ← i

function ctz_debruijn (x)

return table[((x & (-x)) × 0x077CB531) >> 27]

The expression (x & (-x)) again isolates the least-significant 1 bit. There are then only 32 possible words, which the unsigned multiplication and shift hash to the correct position in the table. (Note: this algorithm does not handle the zero input.) A similar algorithm works for log base 2, but rather than isolate the most-significant bit, it rounds up to the nearest integer of the form 2n−1 using shifts and bitwise ORs:[29]

table[0..31] = {0, 9, 1, 10, 13, 21, 2, 29, 11, 14, 16, 18, 22, 25, 3, 30,

8, 12, 20, 28, 15, 17, 24, 7, 19, 27, 23, 6, 26, 5, 4, 31}

function lg_debruijn (x)

for each y in {1, 2, 4, 8, 16}: x ← x | (x >> y)

return table[(x × 0x07C4ACDD) >> 27]

Both the count leading zeros and count trailing zeros operations admit binary search implementations which take a logarithmic number of operations and branches, as in these 32-bit versions:[30][31]

function clz (x)

if x = 0 return 32

n ← 0

if (x & 0xFFFF0000) = 0: n ← n + 16, x ← x << 16

if (x & 0xFF000000) = 0: n ← n + 8, x ← x << 8

if (x & 0xF0000000) = 0: n ← n + 4, x ← x << 4

if (x & 0xC0000000) = 0: n ← n + 2, x ← x << 2

if (x & 0x80000000) = 0: n ← n + 1, x ← x << 1

return n

function ctz (x)

if x = 0 return 32

n ← 0

if (x & 0x0000FFFF) = 0: n ← n + 16, x ← x >> 16

if (x & 0x000000FF) = 0: n ← n + 8, x ← x >> 8

if (x & 0x0000000F) = 0: n ← n + 4, x ← x >> 4

if (x & 0x00000003) = 0: n ← n + 2, x ← x >> 2

if (x & 0x00000001) = 0: n ← n + 1, x ← x << 1

return n

These can be assisted by a table as well, replacing the last four lines of each with a table lookup on the high/low byte.

Just as count leading zeros is useful for software floating point implementations, conversely, on platforms that provide hardware conversion of integers to floating point, the exponent field can be extracted and subtracted from a constant to compute the count of leading zeros. Corrections are needed to account for rounding errors.[30][32]

Applications

The count leading zeros (clz) operation can be used to efficiently implement normalization, which encodes an integer as m × 2e, where m has its most significant bit in a known position (such as the highest position). This can in turn be used to implement Newton-Raphson division, perform integer to floating point conversion in software, and other applications.[33][30]

Count leading zeros (clz) can be used to compute the 32-bit predicate "x=y" (zero if true, one if false) via the identity clz(x-y) >> 5, where ">>" is unsigned right shift.[34] It can be used to perform more sophisticated bit operations like finding the first string of n 1 bits.[35] The expression 16 − clz(x − 1)/2 is an effective initial guess for computing the square root of a 32-bit integer using Newton's method.[36] CLZ can efficiently implement null suppression, a fast data compression technique that encodes an integer as the number of leading zero bytes together with the nonzero bytes.[37] It can also efficiently generate exponentially distributed integers by taking the clz of uniformly random integers.[30]

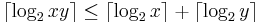

The log base 2 can be used to anticipate whether a multiplication will overflow, since  .[38]

.[38]

Count leading zeros and count trailing zeros can be used together to implement Gosper's loop-detection algorithm,[39] which can find the period of a function of finite range using limited resources.[31]

A bottleneck in the binary GCD algorithm is a loop removing trailing zeros, which can be replaced by a count trailing zeros (ctz) followed by a shift. A similar loop appears in computations of the hailstone sequence.

A bit array can be used to implement a priority queue. In this context, find first set (ffs) is useful in implementing the "pop" or "pull highest priority element" operation efficiently. The Linux kernel real-time scheduler internally uses sched_find_first_bit() for this purpose.[40]

The count trailing zeros operation gives a simple optimal solution to the Tower of Hanoi problem: the disks are numbered from zero, and at move k, disk number ctz(k) is moved the minimum possible distance to the right (circling back around to the left as needed). It can also generate a Gray code by taking an arbitrary word and flipping bit ctz(k) at step k.[31]

Notes

- ^ Anderson, Find the log base 2 of an integer with the MSB N set in O(N) operations (the obvious way)

- ^ a b "FFS(3)". Linux Programmer's Manual. The Linux Kernel Archives. http://www.kernel.org/doc/man-pages/online/pages/man3/ffs.3.html. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ^ a b Intel 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer Manual. Volume 2A: Intel. pp. 3-92 – 3-97. http://www.intel.com/content/www/us/en/processors/architectures-software-developer-manuals.html. Order number 325383.

- ^ AMD64 Architecture Programmer's Manual Volume 3: General Purpose and System Instructions3. AMD. 2011. pp. 204–5. http://support.amd.com/us/Processor_TechDocs/APM_V3_24594.pdf.

- ^ Intel Itanium Architecture Software Developer's Manual. Volume 3: Intel Itanium Instruction Set. Intel. 2010. pp. 3:38. http://www.intel.com/content/www/us/en/processors/itanium/itanium-architecture-vol-3-manual.html.

- ^ "ARM Instruction Reference > ARM general data processing instructions > CLZ". ARM Developer Suite Assembler Guide. ARM. http://infocenter.arm.com/help/index.jsp?topic=/com.arm.doc.dui0068b/CIHJGJED.html. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

- ^ Frey, Brad. PowerPC Architecture Book (Version 2.02 ed.). 3.3.11 Fixed-Point Logical Instructions: IBM. pp. 70. http://www.ibm.com/developerworks/systems/library/es-archguide-v2.html.

- ^ a b MIPS Architecture For Programmers. Volume II-A: The MIPS32 Instruction Set (Revision 3.02 ed.). MIPS Technologies. 2011. pp. 101-102. http://www.mips.com/products/architectures/mips32/.

- ^ a b MIPS Architecture For Programmers. Volume II-A: The MIPS64 Instruction Set (Revision 3.02 ed.). MIPS Technologies. 2011. pp. 105, 107, 122, 123. http://www.mips.com/products/architectures/mips64/.

- ^ a b Alpha Architecture Reference Manual. Compaq. 2002. pp. 4-32, 4-34. http://download.majix.org/dec/alpha_arch_ref.pdf.

- ^ M68000 Family Programmer's Reference Manual. Motorola. 1992. pp. 4-43 – 4-45. http://www.freescale.com/files/archives/doc/ref_manual/M68000PRM.pdf.

- ^ "FFS(3)". Mac OS X Developer Library. Apple, Inc.. 1994 April 19. http://developer.apple.com/library/mac/#documentation/darwin/reference/manpages/10.3/man3/ffs.3.html. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- ^ "FFS(3)". Mac OS X Developer Library. Apple. 2004 January 13. http://developer.apple.com/library/mac/#documentation/darwin/reference/manpages/man3/ffs.3.html. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- ^ "FFS(3)". FreeBSD Library Functions Manual. The FreeBSD Project. http://www.freebsd.org/cgi/man.cgi?query=ffs&apropos=0&sektion=0&manpath=FreeBSD+8.2-RELEASE&arch=default&format=html. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- ^ "5.46 Other built-in functions provided by GCC". Using the GNU Compiler Collection (GCC). Free Software Foundation, Inc.. http://gcc.gnu.org/onlinedocs/gcc-4.1.2/gcc/Other-Builtins.html. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

- ^ "GCC 3.2 Release Series Changes, New Features, and Fixes". GCC 3.2 Release Series. Free Software Foundation, Inc.. http://gcc.gnu.org/gcc-3.2/changes.html. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

- ^ "_BitScanForward, _BitScanForward64". Visual Studio 2005: Visual C++: Compiler Intrinsics. Microsoft. http://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/wfd9z0bb%28VS.80%29.aspx. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

- ^ "_BitScanReverse, _BitScanReverse64". Visual Studio 2005: Visual C++: Compiler Intrinsics. Microsoft. http://msdn.microsoft.com/en-US/library/fbxyd7zd(v=VS.80).aspx. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

- ^ "__lzcnt16, __lzcnt, __lzcnt64". Visual Studio 2008: Visual C++: Compiler Intrinsics. Microsoft. http://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/bb384809(v=VS.90).aspx. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

- ^ Intel C++ Compiler for Linux Intrinsics Reference. Intel. 2006. pp. 21. http://software.intel.com/file/6373.

- ^ NVIDIA CUDA Programming Guide (Version 3.0 ed.). NVIDIA. 2010. pp. 92. http://developer.download.nvidia.com/compute/cuda/3_0/toolkit/docs/NVIDIA_CUDA_ProgrammingGuide.pdf.

- ^ "'llvm.ctlz.*' Intrinsic, 'llvm.cttz.*' Intrinsic". LLVM Language Reference Manual. The LLVM Compiler Infrastructure. http://llvm.org/docs/LangRef.html#int_ctlz. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- ^ Anderson, Round up to the next highest power of 2.

- ^ Blackfin Instruction Set Reference (Preliminary ed.). Analog Devices. 2001. pp. 8-24. Part Number 82-000410-14.

- ^ Dietz, Henry Gordon. "The Aggregate Magic Algorithms". University of Kentucky. http://aggregate.org/MAGIC/#Trailing%20Zero%20Count.

- ^ GerdIsenberg. forward-Index of LS1B by Popcount "BitScanProtected". Chess Programming Wiki. http://chessprogramming.wikispaces.com/BitScan#Bitscan forward-Index of LS1B by Popcount. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

- ^ SPARC International, Inc. (1992). The SPARC architecture manual : version 8 (Version 8. ed.). Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall. pp. 231. ISBN 0-13-825001-4. http://www.sparc.org/standards/SPARCV9.pdf. A.41: Population Count. Programming Note.

- ^ Leiserson, Charles E.; Prokop, Harald; Randall, Keith H. (1998), Using de Bruijn Sequences to Index a 1 in a Computer Word, http://supertech.csail.mit.edu/papers/debruijn.pdf

- ^ Anderson, Find the log base 2 of an N-bit integer in O(lg(N)) operations with multiply and lookup

- ^ a b c d Warren, Section 5-3: Counting Leading 0's.

- ^ a b c Warren, Section 5-4: Counting Trailing 0's.

- ^ Anderson, Find the integer log base 2 of an integer with an 64-bit IEEE float.

- ^ Sloss, Andrew N.; Symes, Dominic; Wright, Chris (2004). ARM system developer's guide designing and optimizing system software (1st ed.). San Francisco, CA: Morgan Kaufman. pp. 212-213. ISBN 1558608745.

- ^ Warren, Section 2-11: Comparison Predicates

- ^ Warren, Section 6-2. Find First String of 1-Bits of a Given Length.

- ^ Warren, 11-1: Integer Square Root.

- ^ Schlegel, Benjamin; Rainer Gemulla, Wolfgang Lehner (June 2010). "Fast integer compression using SIMD instructions". Proceedings of the Sixth International Workshop on Data Management on New Hardware (DaMoN 2010): 34-40. doi:10.1145/1869389.1869394.

- ^ Warren, Section 2-12. Overflow Detection.

- ^ Gosper, Bill (1972). "Loop detector". HAKMEM (239): Item 132. http://www.inwap.com/pdp10/hbaker/hakmem/flows.html#item132.

- ^ Aas, Josh (2005). Understanding the Linux 2.6.8.1 CPU Scheduler. Silicon Graphics, Inc.. pp. 19. http://www.inf.ed.ac.uk/teaching/courses/os/prac/lcpusched-fullpage-2x1.pdf.

References

- Warren, Henry S. (2003). Hacker's Delight (1st ed.). Boston, Mass.: Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0201914654.

- Anderson, Sean Eron. "Bit Twiddling Hacks". Sean Eron Anderson student homepage. Stanford University. http://graphics.stanford.edu/~seander/bithacks.html. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

External links

- Bit Twiddling Hacks, Sean Eron Anderson, Stanford University. Lists several efficient public domain C implementations for count trailing zeros and log base 2.

- Chess Programming Wiki: BitScan: A detailed explanation of a number of implementation methods for ffs (called LS1B) and log base 2 (called MS1B).